How Do The Tories Tackle Their "You Had 14 Years To Do That" Problem?

Kemi Badenoch’s speech yesterday was an excellent one. It acknowledged the mistakes of both the Conservatives in government and of the broader political class of providing “policy without a plan” - something which I touched upon in my essay about Wading Through The Interregnum last week.

The speech also emphasised the need to rebuild trust. A priority for the Tory Party and for British politics as a whole. As Katy Balls argues in her Spectator column this morning, it’s also a reminder of the challenge that an opposition party faces in getting heard above the din. This is a particularly acute challenge now that Reform are also making noise as well as the government. And President Trump (and Elon Musk) can probably also be relied upon to create alternative sources of noise…

I was midway through writing a note about how the Tories can overcome the “you had 14 years to do this” problem when I saw the speech was billed. Yesterday’s speech illustrates that the LOTO team are aware of the problem. But that, obviously doesn’t make it any easier to solve. Little doubt that the speech was a good start, but I think this note remains relevant.

How do the Tories solve the “you had 14 years to do this” problem?

Electorates have long memories. The mistakes that a party makes in government aren’t simply forgotten when a party is ejected to the Opposition benches.

Just look at how political parties have campaigned in elections in recent decades. The Winter of Discontent was still used by the Conservatives in 1992. Labour were still using memories of Black Wednesday, recession and decaying public services in the 2005 campaign. And the Tories were still desperately trying to use that letter from Liam Byrne in the last election although its effectiveness was reduced to less than zero at that point, whereas it was incredibly potent in 2015.

As such, Conservatives will have to work out a way of answering the question “why didn’t you do [insert topic] in your 14 years in power”? Addressing this question will be crucial to them getting comprehensively back in the game.

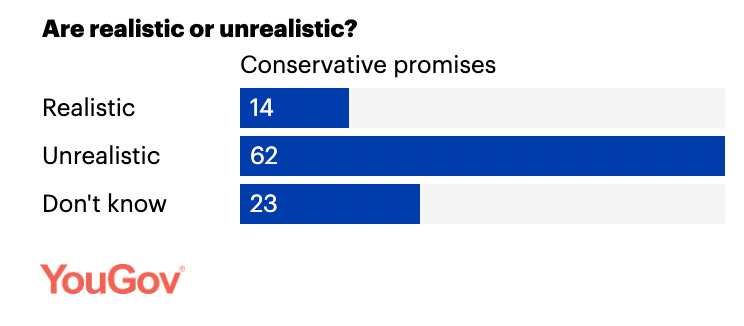

Such a barrier was already clearly in evidence at the last election. The Conservative manifesto was an ambitious collection of promises, which was almost universally met with the doorstep riposte of “you’ve had fourteen years”. This YouGov poll from the last week of the campaign tells the story.

Realignment changes the nature of opposition

Overcoming the “you had 14 years” challenge, while renewing the Party and seeing off Labour and Reform is quite an undertaking. And the realignment and associated fragmentation makes the challenge even harder.

Voters who have generally abandoned traditional party loyalties are less likely to be forgiving of political parties who have not delivered or broken promises in government.

Despite the government’s historically poor polling after 6 months, Conservatives can no longer assume that they will be the default beneficiaries of an anti Labour government vote.

Politics is no longer a binary red v blue. Dissatisfied voters on the right can now tilt towards Reform and on the centre and left have the option of Liberal Democrats, Greens or the independent left.

Geographically too, Conservatives can no longer assume that they will be the default choice for voters dissatisfied with the current government. After the Conservatives spectacularly squandered their 2019 Red Wall gains, Reform are now the major opposition to Labour in swathes of the North and Midlands. And the second wave of the realignment has cemented the Liberal Democrats as a major party across the South.

No Labour honeymoon makes life even trickier

As Luke Tryl of More In Common pointed out on X earlier this week, the lack of any noticeable honeymoon period has a real impact on the Conservatives in opposition.

Last week, the Conservatives dominated the news agenda with their correct call for a national inquiry into grooming gangs. But all of the evidence from both last week and recent months is that Reform and Liberal Democrats are the major beneficiaries from the government’s polling woes. The latest YouGov, for example, found that only 5% of 2024 Labour voters say that they will vote Conservative, compared to 5% for Reform and 7% for the Liberal Democrats.

Conservatives, who still have a tarnished brand from their time in government, seem less likely to benefit from an anti Labour vote than Reform and the Liberal Democrats, who don’t have this tarnished record.

This More In Common voters flow diagram tells a similar story:

In this realignment landscape, the Conservatives need to do what parties emerging into the indignities of opposition have long had to do. But they need to do it more quickly. And louder in order to get attention in a busy and fragmented political environment.

Mea Culpa. Gaining “permission to be heard”

Getting permission to be heard is essential for an Opposition. Voters are unlikely to engage with a Party that has been decisively beaten if they don’t acknowledge the reasons for electoral defeat. Historically, there has been nothing more likely to condemn a party to repeated defeats, such as Labour in the 1950s and 80s and the Tories in the 90s and 2000s, than a belief that it was the voters who were wrong, rather than the political parties.

The Conservatives have to acknowledge that they know why they lost and voters have to feel that atonement is genuine.

It’s clear where voters clearly felt that Conservatives failed to deliver on promises. And many of these issues are those with the highest salience for voters - record immigration after a promise to reduce numbers; a failure to Level Up in the Red Wall; an NHS that seemed strained; and a rising tax burden.

Conservatives have only a small window to acknowledge mistakes and failures and reassure the public that such a failure of delivery cannot be repeated.

In doing so, they have to make clear that the repentance is (and also appears to be) genuine. If you’re doing a Mea Culpa, it’s important that it’s clear that you mean it.

And such a Mea Culpa can’t only come in a single speech. Remember that voters aren’t as politically tuned in as SW1. Instead it should be repeated often enough that its clarity and authenticity have cut through with the public.

Then, and only then, will the Conservatives have gained “permission to be heard” with the public. And their goal then should be to turn current negatives into future positives, with Conservatives having the credibility to put forward policies that accord with public priorities.

Don’t go too far. Don’t trash the brand

It is, of course, possible to go too far and be seen as spending the entire first few years in Opposition denigrating your record in government. This is clearly counterproductive. Acknowledging errors gives a losing party permission to be heard again. It doesn’t give the losing party permission to spend years lambasting their predecessor for not being conservative enough/ socialist enough. That just makes you seem like a self-interested rabble.

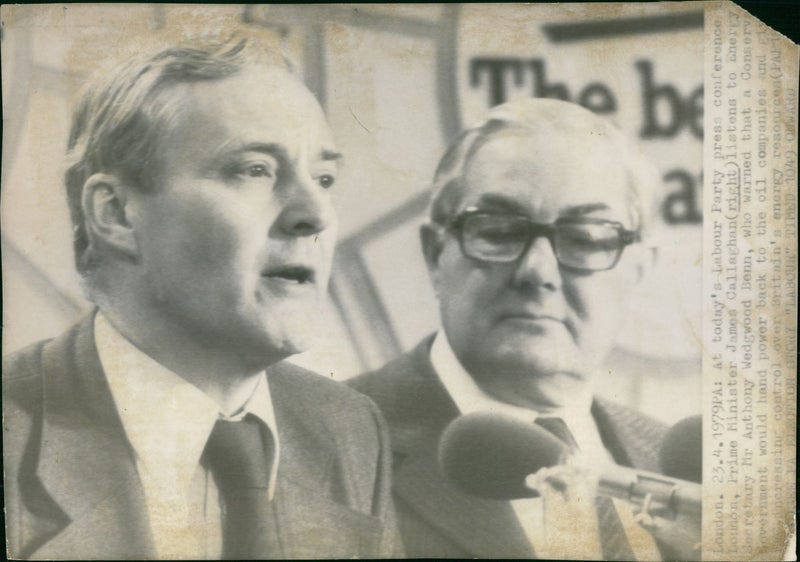

There are two great examples of this. The first, which is visually the most striking is Tony Benn at the 1979 Labour conference reading out a long list of the promises that the recently ejected government (of which he was a member) had failed to deliver. And he was cheered on by delegates, with a stern-faced Shadow Cabinet, included Jim Callaghan, sitting behind in. It looked chaotic, extreme and divided and helped to further tarnish the brand.

Similarly, Ed Miliband’s constant denunciation of New Labour (a government in which he was at first an adviser and then a Minister) seemed more aimed at tarnishing the New Labour brand than building an alternative. It was a reckless thing to do given New Labour’s remarkable electoral success in comparison to Miliband’s soft-leftism.

By contrast, an acknowledgement of past mistakes must be clear and decisive but also attached with a reminder of the successes of the previous government. An effort to repair the brand will be less successful if accompanied with broadbrush and indiscriminate attacks on the same brand. It’s more successful when showing that a political party is again aligned with the values of the public.

Building a reputation for trust and competence

As the Tories found out last July, political promises are pointless if the public have no trust in your ability to deliver them. One element is ensuring public trust in the willingness of a political party to fulfil their promises. Another is believing that a political party has the competence to deliver on their promises. A third is ensuring that the values your policies and pronouncements espouse are aligned with the values of the voters that you are trying to persuade.

The Conservative brand in the early New Labour years was so weak because voters believed that the party didn’t share their values and didn’t have the competence to implement their policies. Famously, Lord Ashcroft’s Smell The Coffee in 2025 found that voters were much less likely to agree with a policy when they found out that it was a Tory policy. It also contained this graph showing how tainted the Tory brand was eight years after Tony Blair’s initial landslide, with most voters still thinking the Party hadn’t learned from its mistakes and wouldn’t deliver on its promises.

The challenge for the Conservatives now is to quickly instil in the voters’ minds that they have learned from their mistakes and ensure that voters believe that they have the competence to deliver.

Building a vision

What will a Tory Britain look like five years after an election win? What will be its defining characteristics?

Kemi Badenoch is right not to make detailed policies five years out from an election. Most successful opposition leaders backed away from detailed policy in the first few years of their leadership too. But is is important for the Party to identify what the principles are on which these policies can be based.

In particular, what would a Tory government mean for the economy, immigration and public services? Once voters can picture the contours of what a Tory Britain might look like, they will be more inclined to give the party a hearing.