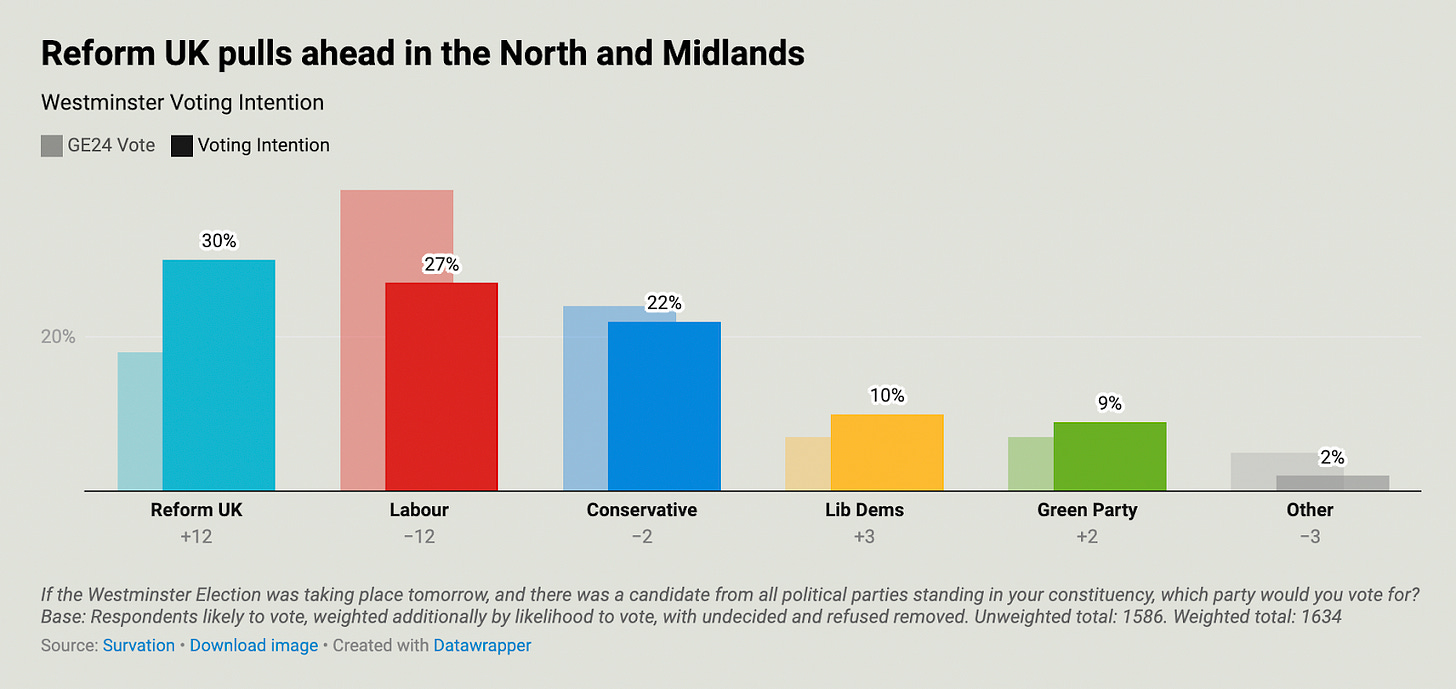

The front page of last Wednesday’s Sun splashed with news of an opinion poll that suggested Reform were likely to do very well in the so called Red Wall, both in upcoming local elections and in any general election. The Survation poll reaffirmed the findings of JL Partners recent “Polaris model” that showed Reform set to sweep the Red Wall.

It’s confirmation that Nigel Farage’s party is extremely well placed in those Northern and Midlands seats that were once solidly Labour. Reform are second in 98 seats and 89 of these are where they are second to Labour in these Red Wall seats.

Reform’s sensible decision to nod towards economic interventionism when necessary suggests that they understand the importance of winning economically interventionist, socially conservative voters in the Midlands and the North. And the importance of being ideologically agile in order to do this.

The hope is that any party with an electoral strategy that centres around the Red Wall accompanies this with an economic and policy strategy that genuinely aims to turn Forgotten Towns around. Red Wall voters deserve more than simply being seen as a reliable source of votes based on disenchantment, then hope, then rapidly dashed hope. Seb Payne’s excellent column in The Times last week asked the important question of what will happen if Red Wall voters are let down again.

As someone who has devoted an enormous amount of personal and political energy in placing the Red Wall at the centre of the political conversation, I’m delighted that it remains a “swing region”. But, having placed a good amount of that energy on persuading Conservatives that they should take Red Wall seats seriously, it’s also given me pause to step back and consider how the Conservatives squandered an opportunity to redraw the political map.

The Tories and The Red Wall. Where Did It All Go Wrong?

Seeing Reform and Labour scrapping it out for dominance in the Red Wall, must have sensible Tories reaching for that perhaps apocryphal George Best related question: “Where did it all go wrong?”

It is, after all, still only six and a half years since the Conservatives made the kind of inroads into once solid Labour territory that saw the Guardian claiming the election was “one of the most significant moments in postwar politics” that “signifies a realignment of postwar politics.” The then Prime Minister described the victory as “stonking” and promised to the new working class Tory voters, whose pencils may have “quivered over the ballot paper” that the government would “never take your support for granted.”

We know how that story ended. The Red Wall turned Red again almost in its entirety in 2024. Tory MPs plummeted from first to third place in dozens of seats across the North and Midlands.

Conservative commentators, clutching at crutches for comfort, persuaded themselves that the unravelling of the Realignment was inevitable. They argued that the election of 2019 was explained purely by “Getting Brexit Done” and working class revulsion at Jeremy Corbyn’s peacenik politics.

These commentators couldn’t be more wrong. As we’ve noted previously on this Substack, the Realignment is the result of longer-term political and social trends and the gradual (and then sudden) erosion of traditional partisan loyalty to Labour in many post-industrial communities. These long-term trends remain, as does the erosion of tribal loyalty. Indeed, Labour’s vote actually fell in 31 of the Red Wall seats it won back. The Tories turned their back on the Red Wall long before the Red Wall turned its back on the Tories.

Why the Conservatives lost the Red Wall

Put simply, Conservatives lost the Red Wall because they were, ultimately, unwilling to put in the hard work necessary to keep it in the Conservative column. They were unwilling to move far enough, for long enough, from their ideological comfort zone to being about the change that they had promised Northern voters.

There is much more to be written on this over the coming months and years, given that the Conservatives failure to build on 2019 will go down as a historic missed opportunity. But this Substack will only consider why the Conservatives blew it and why it matters.

In his first major speech as Prime Minister, Boris Johnson talked about the post-industrial towns that had seen decades of decline. He argued that:

the crucial point is it isn’t really the fault of the places and it certainly isn’t the fault of the people growing up there - they haven’t failed. No, it is we, us the politicians, the politics, that has failed…Time and again they have voted for change, but for too long politicians have failed to deliver on what is needed.

Fundamental to this was the understanding that voters in the North had heard big promises before and that politicians had “failed to deliver on what is needed.” If the Tories were to consolidate the realignment then they needed to deliver more than a Brexit deal.

The voters who voted Tory for the first time in 2019 expected the Party to meet their promise that “overall [immigration] numbers will come down”, they expected Levelling Up to be showing signs of turning round regional inequality and the beginning of steps to reindustrialise parts of the country. Like all voters, they also wanted to see better public services. In other words, they wanted action to match big promises.

Sadly, none of these promises were delivered. I’ve written at length (as have many others) about the failure to deliver on promises to lower immigration and the failure to deliver on four consecutive manifesto promises to either “reduce immigration to the tens of thousands” (in 2010, 2015 and 2017) or ensure that overall “numbers will come down” in 2019. Instead, we say two years of record immigration. It’s a failure to deliver that is having a lasting impact on towns throughout the country.

The Tory Party entered the 2019-24 Parliament with Levelling Up as a core part of its mission. By the time of the 2024 rout, the concept was barely mentioned at all, with a retreat to a narrow austerity and small-statism that didn’t really seem to inspire many voters at all. It certainly didn’t inspire voters in the Red Wall

Reversing entrenched and long-standing regional inequalities was going to need government to think big and get the whole of the governmental machine behind a core goal. Sadly, the Treasury view meant that ambitious or transformative projects were often frowned upon, with one eye on the Treasury abacus. Although the Levelling Up White Paper was spot on in terms of both diagnosis and solution, the lack of cross government backing and adequate resources meant that goals were always unlikely to be entirely met. And, as George Osborne and Ed Balls frequently make clear in their excellent podcast, there is next to zero chance of getting anything done in the UK without strong Treasury backing and cross-governmental prioritisation.

An ambitious programme that could have produced a metamorphic change in the British economy was replaced with well meaning, but small scale projects that generally failed to move the dial. Levelling Up also faced the challenge of a government trying to renew itself while in power, meaning that the years of planning and coalition building that went into policies such as the 2010 education reforms, for example, couldn’t be replicated in this case.

A failure to show ideological agility

Generally transforming the British economy would have required the Conservatives to show ideological agility, including in pursuit of industrial policy designed to reindustrialise and in the intelligent use of the state where it was necessary. When it came to shift from concept and slogan to reality, Conservatives weren’t always willing to give full-throated backing to policies that involved spending on infrastructure, development of industrial policy and effective and intelligent use of the state. And when conditions became more difficult and leadership changed, the project lacked sufficient Parliamentary champions, or even Conservative champions outside of Parliament, to sustain much needed momentum.

The lack of “true believers” in both Realignment and Levelling Up meant that it was never properly part of the DNA of the Conservative Party either inside or outside of Parliament. When it came down to the 2022 leadership election, both candidates in the final round made it clear that they didn’t want to prioritise tackling Britain’s regional inequalities (as I wrote at the time for The New Statesman). Liz Truss’s comic book libertarianism had no room for the intelligent use of the state that Levelling Up and reindustrialisation needed. Rishi Sunak’s austerity and neo-liberalism was also barely consistent with attempts to turn around regional decline.

Hence, the 2019 mandate of 14 million voters for Levelling Up and reindustrialisation was regarded as being less important than the “mandate” of 80,000 Tory Party members. A Parliament that started with bold promises to do whatever it takes to rebuild the economies of the North and the Midlands ended with the short-sighted cancellation and the collapse of the Red Wall.

For voters in the North and Midlands, the 2019 Tories had become yet another set of politicians who promised much but “failed to deliver what is needed.”

Conservatives can’t ignore the Red Wall forever

In the post 2024 environment, many Conservatives might be content to let Labour and Reform battle it out for the Red Wall, while they retreat into selling Margaret Thatcher mugs to true believers and staying close to their ideological comfort zone.

But that ignores the electoral geography of modern Britain. As with so many elements in modern British politics, Brexit changed everything. It meant that once safe Conservative seats and hard-fought marginals in suburbs and on the edge of the Home Counties are now out of reach for the Party.

The JL Partners Polaris survey, as well as the election result of last year, showed that without the Red Wall, Conservatives are restricted to generally very rural seats, leaving them miles away from being able to win a parliamentary majority.

This means that Conservatives have two choices to become a force pushing for an overall majority again. The first is to pursue some kind of CDU/ CSU relationship with Reform, but this obviously has numerous downsides, as well as a lack of control. The second, and most sustainable, is to again make an effort to appeal to working class voters in the Red Wall. They should use their time in opposition to develop credible plans to reindustrialise, to set out how they will deliver badly needed major infrastructure programmes and to grow the private sector in lagging regions.

The Red Wall is still very much up for grabs. Conservatives need to start taking it seriously again.

From where I'm standing right now, the "red wall" and "blue wall" seem more-or-less equally out-of-reach for the party.